How Meta Is Leveraging AI To Improve the Quality of Scope 3 Emission Estimates for IT Hardware

- As we focus on our goal of achieving net zero emissions in 2030, we also aim to create a common taxonomy for the entire industry to measure carbon emissions.

- We’re sharing details on a new methodology we presented at the 2025 OCP regional EMEA summit that leverages AI to improve our understanding of our IT hardware’s Scope 3 emissions.

- We are collaborating with the OCP PCR workstream to open source this methodology for the wider industry. This collaboration will be introduced at the 2025 OCP Global Summit.

As Meta focuses on achieving net zero emissions in 2030, understanding the carbon footprint of server hardware is crucial for making informed decisions about sustainable sourcing and design. However, calculating the precise carbon footprint is challenging due to complex supply chains and limited data from suppliers. IT hardware used in our data centers is a significant source of emissions, and the embodied carbon associated with the manufacturing and transportation of this hardware is particularly challenging to quantify.

To address this, we developed a methodology to estimate and track the carbon emissions of hundreds of millions of components in our data centers. This approach involves a combination of cost-based estimates, modeled estimates, and component-specific product carbon footprints (PCFs) to provide a detailed understanding of embodied carbon emissions. These component-level estimates are ranked by the quality of data and aggregated at the server rack level.

By using this approach, we can analyze emissions at multiple levels of granularity, from individual screws to entire rack assemblies. This comprehensive framework allows us to identify high-impact areas for emissions reduction.

Our ultimate goal is to drive the industry to adopt more sustainable manufacturing practices and produce components with reduced emissions. This initiative underscores the importance of high-quality data and collaboration with suppliers to enhance the accuracy of carbon footprint calculations to drive more sustainable practices.

We leveraged AI to help us improve this database and understand our Scope 3 emissions associated with IT hardware by:

- Identifying similar components and applying existing PCFs to similar components that lack these carbon estimates.

- Extracting data from heterogeneous data sources to be used in parameterized models.

- Understanding the carbon footprint of IT racks and applying generative AI (GenAI) as a categorization algorithm to create a new and standard taxonomy. This taxonomy helps us understand the hierarchy and hotspots in our fleet and allows us to provide insights to the data center design team in their language. We hope to iterate on this taxonomy with the data center industry and agree on an industry-wide standard that allows us to compare IT hardware carbon footprints for different types and generations of hardware.

Why We Are Leveraging AI

For this work we used various AI methods to enhance the accuracy and coverage of Scope 3 emission estimates for our IT hardware. Our approach leverages the unique strengths of both natural language processing (NLP) and large language models (LLMs).

NLP For Identifying Similar Components

In our first use case (Identifying similar components with AI), we employed various NLP techniques such as Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) and Cosine similarity to identify patterns within a bounded, relatively small dataset. Specifically, we applied this method to determine the similarity between different components. This approach allowed us to develop a highly specialized model for this specific task.

LLMs For Handling and Understanding Data

LLMs are pre-trained on a large corpus of text data, enabling them to learn general patterns and relationships in language. They go through a post-training phase to adapt to specific use cases such as chatbots. We apply LLMs, specifically Llama 3.1, in the following three different scenarios:

- To extract and process information from diverse data sources. The benefit of LLMs is that the model can recognize different representations of the same information, even if formatted or phrased differently. (see section: Extracting Data From Heterogeneous Data)

- To understand potential groupings of components, aiding in the creation of a new taxonomy. (see section: A Component-Level Breakdown of IT Hardware Emissions Using AI)

- Once categories are identified, we use an LLM to strictly classify components based on text strings. This method allows us to save significant training time compared to a traditional AI model, as LLMs can be quickly prompt-engineered to handle various tasks. (see section: A Component-Level Breakdown of IT Hardware Emissions Using AI)

Unlike the first use case, where we needed a highly specialized model to detect similarities, we opted for LLM for these three use cases because it leverages general human language rules. This includes handling different units for parameters, grouping synonyms into categories, and recognizing varied phrasing or terminology that conveys the same concept. This approach allows us to efficiently handle variability and complexity in language, which would have required significantly more time and effort to achieve using only traditional AI.

Identifying Similar Components With AI

When analyzing inventory components, it’s common for multiple identifiers to represent the same parts or slight variations of them. This can occur due to differences in lifecycle stages, minor compositional variations, or new iterations of the part.

PCFs following the GHG Protocol are the highest quality input data we can reference for each component, as they typically account for the Scope 3 emissions estimates throughout the entire lifecycle of the component. However, conducting a PCF is a time-consuming process that typically takes months. Therefore, when we receive PCF information, it is crucial to ensure that we map all the components correctly.

PCFs are typically tied to a specific identifier, along with aggregated components. For instance, a PCF might be performed specifically for a particular board in a server, but there could be numerous variations of this specific component within an inventory. The complexity increases as the subcomponents of these items are often identical, meaning the potential impact of a PCF can be significantly multiplied across a fleet.

To maximize the utility of a PCF, it is essential to not only identify the primary component and its related subcomponents but also identify all similar parts that a PCF could be applied to. If these similar components are not identified their carbon footprint estimates will remain at a lower data quality. Therefore, identifying similar components is crucial to ensure that we:

- Leverage PCF information to ensure the highest data quality for all components.

- Maintain consistency within the dataset, ensuring that similar components have the same or closely aligned estimates.

- Improve traceability of each component’s carbon footprint estimate for reporting.

To achieve this, we employed a natural language processing (NLP) algorithm, specifically tailored to the language of this dataset, to identify possible proxy components by analyzing textual descriptions and filtering results by component category to ensure relevance.

The algorithm identifies proxy components in two distinct ways:

- Leveraging New PCFs: When a new PCF is received, the algorithm uses it as a reference point. It analyzes the description names of components within the same category to identify those with a high percentage of similarity. These similar components can be mapped to a representative proxy PCF, allowing us to use high-quality PCF data in similar components.

- Improving Low Data Quality Components: For components with low data quality scores, the algorithm operates in reverse with additional constraints. Starting with a list of low-data-quality components, the algorithm searches for estimates that have a data quality score greater than a certain threshold. These high-quality references can then be used to improve the data quality of the original low-scoring components.

Meta’s Net Zero team reviews the proposed proxies and validates our ability to apply them in our estimates. This approach enhances the accuracy and consistency of component data, ensures that high-quality PCF data is effectively utilized across similar components, and enables us to design our systems to more effectively reduce emissions associated with server hardware.

Extracting Data From Heterogeneous Data Sources

When PCFs are not available, we aim to avoid using spend-to-carbon methods because they tie sustainability too closely to spending on hardware and can be less accurate due to the influence of factors like supply chain disruptions.

Instead, we have developed a portfolio of methods to estimate the carbon footprint of these components, including through parameterized modeling. To adapt any model at scale, we require two essential elements: a deterministic model to scale the emissions, and a list of data input parameters. For example, we can scale the carbon footprint calculation for a component by knowing its constituent components’ carbon footprint.

However, applying this methodology can be challenging due to inconsistent description data or locations where information is presented. For instance, information about cables may be stored in different tables, formats, or units, so we may be unable to apply models to some components due to difficulty in locating input data.

To overcome this challenge, we have utilized large language models (LLMs) that extract information from heterogeneous sources and inject the extracted information into the parameterized model. This differs from how we apply NLP, as it focuses on extracting information from specific components. Scaling a common model ensures that the estimates provided for these parts are consistent with similar parts from the same family and can inform estimates for missing or misaligned parts.

We applied this approach to two specific categories: memory and cables. The LLM extracts relevant data (e.g., the capacity for memory estimates and length/type of cable for physics-based estimates) and scales the components’ emissions calculations according to the provided formulas.

A Component-Level Breakdown of IT Hardware Emissions Using AI

We utilize our centralized component carbon footprint database not only for reporting emissions, but also to drive our ability to efficiently deploy emissions reduction interventions. Conducting a granular analysis of component-level emissions enables us to pinpoint specific areas for improvement and prioritize our efforts to achieve net zero emissions. For instance, if a particular component is found to have a disproportionately high carbon footprint, we can explore alternative materials or manufacturing processes to mitigate its environmental impact. We may also determine that we should reuse components and extend their useful life by testing or augmenting component reliability. By leveraging data-driven insights at the component level and driving proactive design interventions to reduce component emissions, we can more effectively prioritize sustainability when designing new servers.

We leverage a bill of materials (BOM) to list all of the components in a server rack in a tree structure, with “children” component nodes listed under “parent” nodes. However, each vendor can have a different BOM structure, so two identical racks may be represented differently. This, coupled with the heterogeneity of methods to estimate emissions, makes it challenging to easily identify actions to reduce component emissions.

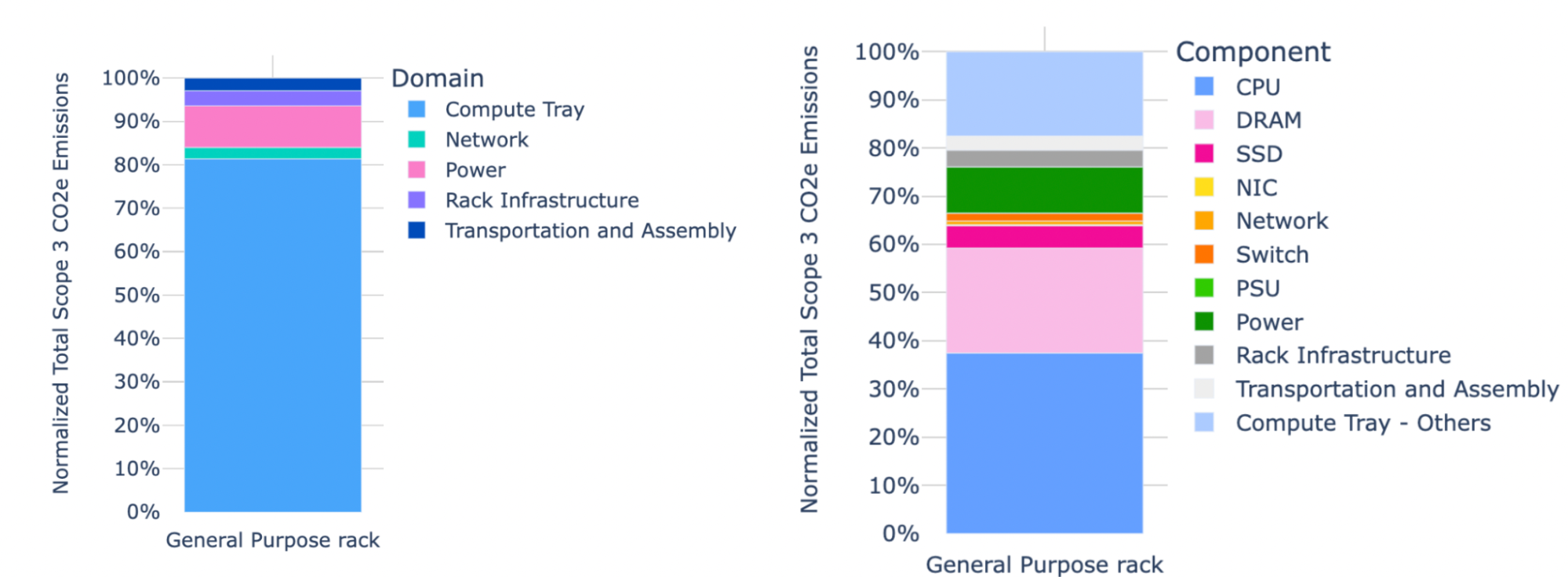

To address this challenge, we have used AI to categorize the descriptive data of our racks into two hierarchical levels:

- Domain-level: A high-level breakdown of a rack into main functional groupings (e.g., compute, network, power, mechanical, and storage)

- Component-level: A detailed breakdown that highlights the major components that are responsible for the bulk of Scope 3 emissions (e.g., CPU, GPU, DRAM, Flash, etc.)

We have developed two classification models: one for “domain” mapping, and another for “component” mapping. The difference between these mappings lies in the training data and the additional set of examples provided to each model. We then combine the two classifications to generate a mutually exclusive hierarchy.

During the exploration phase of the new taxonomy generation, we allowed the GenAI model to operate freely to identify potential categories for grouping. After reviewing these potential groupings with our internal hardware experts, we established a fixed list of major components. Once this list was finalized, we switched to using a strict GenAI classifier model as follows:

- For each rack, recursively identify the highest contributors, grouping smaller represented items together.

- Run a GenAI mutually exclusive classifier algorithm to group the components into the identified categories.

This methodology has been presented at the 2025 OCP regional EMEA summit with the goal to drive the industry toward a common taxonomy for carbon footprint emissions, and open source the methodology we used to create our taxonomy.

These groupings are specifically created to aid carbon footprint analysis, rather than for other purposes such as cost analysis. However, the methodology can be tailored for other purposes as necessary.

Coming Soon: Open Sourcing Our Taxonomies and Methodologies

As we work toward achieving net zero emissions across our value chain in 2030, this component-level breakdown methodology is necessary to help understand our emissions at the server component level. By using a combination of high-quality PCFs, spend-to-carbon data, and a portfolio of methods that leverage AI, we can enhance our data quality and coverage to more effectively deploy emissions reduction interventions.

Our next steps include open sourcing:

- The taxonomy and methodology for server rack emissions accounting.

- The taxonomy builder using GenAI classifiers.

- The aggregation methodology to improve facility reporting processes across the industry.

We are committed to sharing our learnings with the industry as we evolve this methodology, now as part of a collaborative effort with the OCP PCR group.

The post How Meta Is Leveraging AI To Improve the Quality of Scope 3 Emission Estimates for IT Hardware appeared first on Engineering at Meta.

Login to comment

LoginRelated Conversations

-

Design for Sustainability: New Design Principles for Reducing IT Hardware Emissions

0 Replies

-

OCP Summit 2025: The Open Future of Networking Hardware for AI

0 Replies

-

Scaling Privacy Infrastructure for GenAI Product Innovation

0 Replies

-

10X Backbone: How Meta Is Scaling Backbone Connectivity for AI

0 Replies

-

Scaling LLM Inference: Innovations in Tensor Parallelism, Context Parallelism, and Expert Parallelism

0 Replies